-

WFL

-

1974 Season

-

1975 Season

-

Multimedia

1974 WFL Team Pages

Jacksonville Sharks

| Owner | Francis Monaco |

| General Manager | Lewis Engelberg |

| Head Coach | Bud Asher/Charlie Tate |

| Stadium | Gator Bowl (72,000) |

| Colors | Black, Silver |

The Jacksonville Sharks joined the WFL when owner Francis Monaco decided to enter professional sports and purchase a franchise for the city of Jacksonville, Florida.. Monaco had made a small fortune running a chain of successful medical laboratories and was also close to some of the NFL elite. Monaco also co-owned a restaurant with former NFL great Dick Butkus. Monaco bought the WFL's Miami franchise from Chuck Rohe and relocated the ream in Jacksonville. Jacksonville, located on the northern Atlantic coast of Florida was a football hotbed. College football games drew enormous crowds of fans and Monaco, a seasoned businessman was ready to cash in.

The team dropped a public relations bomb when they introduced the teams' nickname as the "Sharks". The tourist board of Florida petitioned the club to change the name, claiming it would be bad for tourism. The board even suggested the team be called the "Stingrays" or the "Suns". Francis Monaco refused and the W.F.L. welcomed the Jacksonville Sharks. Monaco hired Bud Asher to coach the team. Asher, who had been out of coaching for some time, quickly went to scout area talent for the club. Jacksonville signed running back Tommy Durrance, a local college star at Florida, and Greg Townsend a standout defensive back for Notre Dame.

If experience counted the Sharks could have ordered their World Bowl rings during training camp. The Sharks had over 40 players on the roster with pro football experience. The offense centered on quarterback Kay Stephenson, a veteran of the NFL with San Diego and Buffalo, and backup Kim Hammond. The running game was handed to Florida star Tommy Durrance, Edgar Scott and Wayne Jones. The receiver corps was led by Drew Buie and tight end Dennis Hughes. The Shark offensive line consisted of veteran guards O.Z. White, Richard Cheek, and rookie Eddie Foster. The tackle position saw Brian Galloway, Willie Blackmon, Steve Schaap and Darrell Vaughn competing for a starting position.

Defensively the Sharks have three veterans up front; Frank Cornish, ex-NFL Buffalo Bill Bob Taterak and Willie Crittenden. The linebackers consist of Glen Gaspard, Lonnie Coleman and Gary Potempa. The secondary was solid with veterans Alvin Wyatt, Solomon Brennan and All-American rookie Greg Townsend from Notre Dame. Jacksonville also planned for the future, signing Miami Dolphin star linebacker Nick Buoniconti to a contract for the 1976 season.

As the Sharks worked through the summer Florida heat, Coach Asher and his assistants quickly settled the teams' playbook and prepared for their opening game against New York. The Sharks played the New York Stars before a nationally televised audience, and 59,112 screaming fans at the Gator Bowl. Inside the games' inaugural program Monaco wrote; "In a few short months the Sharks have gone from a dream to a reality and it has been at times a tedious transition... Our goal this first season is to achieve the championship plateau only one team can finally attain." After the first half, which saw both teams struggle to find consistency with their offense, the game had a 20-minute blackout when a generator fire broke out and knocked out the stadiums' lights. Standing in the dark, Shark coach Bud Asher wondered if the blackout was an omen. It wasn't. When play resumed, Sharks defensive back Alvin Wyatt returned a punt for a touchdown, and guard O.Z. White recovered a fumbled in the end zone for another score to lead the Sharks to a 14-7 victory and take the first step towards making Monaco's "dream" a reality. After the game, the Jacksonville press flooded the Sharks dressing room with questions for their hometown heroes had dealt the Stars, featuring ex-NFL greats John Elliott, Garry Philbin and George Sauer, their first WFL loss. WFL commissioner Gary Davidson, in attendance, was in awe of the turnout and talked about the potential success of the franchise and the league.

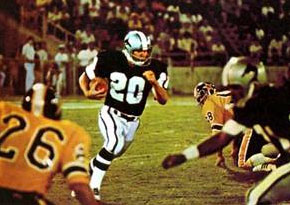

Shark Tommy Durrance runs against the New York Stars in the WFL opener

With a 1-0 record, Jacksonville's second game of the season, in Chicago, was also a close contest. Another incredible crowd of almost 30,000 watched as Shark quarterback Kay Stephenson threw a touchdown pass to Joe Thornton for a 22-15 Jacksonville lead in the third quarter. Then the Chicago Fire came back. In the final minutes the Fire blew a field goal attempt when their center, Mick Heinrich, lost a contact lens and sent the hike rolling along the ground. Fire defensive back and place holder Joe Womack, panicked, picked up the arrant snap and ran the ball to the one yard line for a first down. Chicago then scored on a 1-yard Mark Kellar run to tie the game at 22-22. With Asher pacing the sidelines, Fire quarterback Virgil Carter and running back Bob Wyatt led Chicago down the field into Shark territory. Then a crucial interference call brought the drive closer for Chuck Ramsey's field goal to win 25-22 with: 06 remaining. All Bud Asher could say after the game was a simple "no comment".

The Sharks returned to Florida with a 1-1 won-lost record, and then the team began a tradition of losing close games. Over 40,000 fans (46,780) attended the Sharks' second home game against the Southern California Sun (although it had been reported that almost 15,000 tickets had been given away) and, as in Chicago, Jacksonville lost in the final minutes. The Sharks moved the ball well against the Sun but couldn't get to the end zone. Kicker Grant Guthrie booted field goals of 23, 29, 27 and 42 yards for a 12-0 Shark lead. The Sharks kept after Sun quarterback Tony Adams with a defensive line that was manned entirely by NFL veterans, including Ike Lassiter (11 years in the NFL) and Bob Taterak (7 years). The pressure caused Adams to run for cover most of the game. The Sharks dominated the Sun, allowing their "star" backfield of Kermit Johnson and James McAllister only 2 yards rushing in the first half, compared to 162 for Jacksonville. "They were throwing a defense at us we hadn't seen and they blitzed a lot," said Adams.

The Sharks scratched and clawed throughout the game. In an almost eerie turn of events, the Shark patrons at the Gator Bowl were treated to another surprising event. A cargo ship anchored in the St.John's River outside the Gator Bowl exploded and caught fire. For the rest of the quarter, fans rimming the top of the stadium shared their attention between the firefighters and the Sharks. Sun coach Tom Fears wished he was watching the blaze in the harbor instead of the one on the field. The Sun could do nothing right. Punter Steve Schroder fumbled two snaps, Terry Lindsey fumbled a punt return, and Tony Adams threw two interceptions. In the third quarter, the Sun began to come back. Adams hit Dave Williams for a touchdown, and then drove again on the Sharks as Ralph Nelson ran for a 1-yard touchdown and a 15-12 Sun lead.

The Sharks put together their only touchdown drive, an 8-play march that ended with a Kay Stephenson to Tony Lomax scoring pass with 14:56 left in the game. The Gator Bowl erupted and the Sharks had a 19-15 lead. With: 07 showing on the Gator Bowl scoreboard both teams lined up at the Jacksonville 40. The Shark defense had held the Sun on two previous drives and looked to do it one more time. The Sun loaded four receivers on the line of scrimmage, Jacksonville countered with three down linemen (Ike Lassiter, Bob Taterak and Arthur May) and dropped everyone back in a "prevent" defense. As the Sun came to the line, the crowd rose to its feet. 46,000 strong, screaming at the top of their lungs. Adams walked to the line, called the signals. Adams took the snap, dropped back, set, and threw a "prayer shot" into the Jacksonville night. As the gold and orange ball took flight, Adams was rocked by a Jacksonville defender. In the end zone, Dave Williams dove, looking over his shoulder, and somehow, caught the pass through the hands of Shark cornerback Jerry Davis and fell to the ground for the winning score. Southern California won 22-19. The 46,000 Sharks fans fell silent.

In the locker room, the stunned Sharks, who lost the previous week to Chicago by a last-second field goal, sat in silence. Bud Asher, their coach, trembled as he spoke to reporters. "I can't tell you how much this hurts-losing two in a row like that. If we'd scored just one touchdown instead of any of those four field goals, we'd... " His voice faded and he turned away. The Sharks were 1-2.

The Sharks season was already off to an unbelievable start. A blackout in the first game, a fumbled snap and a close loss in Chicago, and a cargo ship fire and a last-second "Hail Mary" loss to the Sun. The Sharks were making the headlines. One of the most interesting moments in Sharks' history occurred the next week below the dim lights of New York's Downing Stadium. The Sharks came to New York with a 1-2 record. After battling the Stars for three quarters the Sharks suffered a huge blow. Quarterback Kay Stephenson was crushed by Star linebacker Gerry Philbin and suffered a knee injury and was forced to leave the game. Coach Bud Asher sent in second string quarterback Kim Hammond. On the first play of the fourth quarter, a blitz by Stars linebacker James Sims cut down Hammond and sent him hard into the Downing Stadium turf. On the next play, linebacker John Elliott sacked Hammond and sent him out of the game with a concussion.

On the Jacksonville sidelines, Coach Bud Asher searched for answers. He wanted to play John Stofa, an inactive quarterback, but that would have resulted in a forfeit due to his inability to dress an inactive player. Asher looked down the bench and pointed to Jeff Davis. Davis, a running back, was from a little-known school ( Name Mars Type Hill Type College), and had the dubious honor of being the 441st player drafted in the 442 player N.F.L. draft. Davis knew the offense, and even though it was only his second game with the team since joining the squad. Asher gave him the nod and Davis entered the game. In a startled Sharks huddle, Davis called plays that Asher sent in to keep the Stars off balance. Davis drove the Sharks down the field with a mixture of quarterback option plays and long passes. The Stars were baffled. They couldn't mentally make the adjustment to this small scrambling quarterback. The 24-year-old rookie moved the Sharks to the Stars' 9-yard line, then again to their 23, but he missed on several passes for the win. On one play, Davis thought he had a touchdown pass to wide receiver Tony Lomax but officials ruled that Lomax caught the ball out of bounds. The Sharks lost to the Stars 24-16. After the game Davis told reporters, "He was in. The official made a bad call. It's no wonder he didn't see it considering the lighting system here!" The Sharks were now 1-3.

On August 8, 1974, reports surfaced regarding WFL attendance figures. The World Football League had built a careful image around the fact it had successful attendance figures in the first weeks of the season. In Philadelphia, the Bell, announced that out of 120,000 fans who came to see the teams' first two games, only 20,000 actually paid to get in. In Jacksonville, Executive Vice President of the Sharks, Danny Bridges, said that out of the 105,892 fans that saw the Sharks first two home games, about 44,000 got in for free. Owner Fran Monaco rebutted the statement claiming that 14,000 had been sold at "reduced rates". "We are a new league," said Monaco. "And I have to come to Jacksonville to try and build something that not only Fran Monaco can be proud of, but the city as well. Why shouldn't I be allowed to let in the youth of Jacksonville... and at the same time display my product to the parents who accompany these children? Let's not forget that its' my money, my worry and my expense going into this venture." Despite the attendance figures and the complimentary tickets, the Sharks and the WFL were still considered a success- although now suspect to media scrutiny.

On August 9, 1974, the Sharks hosted the Hawaiians at the Gator Bowl. 43,869 fans, another strong crowd, came out to the stadium. With the Sharks' quarterbacks injured, Asher started Georgia Tech rookie Eddie McAshan. McAshan, who missed the Sharks first four games with a shoulder injury, took two quarters to get warmed up and then mixed passes and outside option runs to puzzle the Hawaiians. McAshan hit Keith Krepfle with a 31-yard pass, and Drew Buie with a 24-yarder to keep a Sharks alive in the fourth quarter. Trailing 14-6, Shark running back Name Ricky Name Lake pounded over from the 2 to tie the game at 14-14.

Bud Asher paced nervously on the sidelines. His team had a knack for self-destructing at the last minute, and Hawaii had the hot hand of quarterback Norris Weese and the weapons to score. But the Shark defense held, giving the offense another shot at a win. With 5:29 left in the game McAshan started the teams' drive at their 20. McAshan hit Keith Krepfle with an 11-yard pass to the 31. Then McAshan dropped back and hit receiver Drew Buie with an 11-yard pass to midfield. The Shark bench came alive. Coach Bud Asher was screaming in instructions and the players were on their feet for a glimpse of the action. McAshan began sweeping right and left, either flipping the ball to Tommy Durrance (the leading rusher in the WFL) or keeping it and ripping off first downs. The Hawaiians were helpless to stop the onslaught. Darting through the middle of the line, McAshan got the ball to the Hawaii one yard line.

:20 showed on the Gator Bowl scoreboard. From the huddle, a calm Eddie McAshan looked around at his team mates and called the play, a "quarterback keeper". The 40,000 Shark fans sounded like a thundering herd, as the Jacksonville players came to the line. The Hawaiians dug in. The front four of Karl Lorch, Ron East, Levi Stanley and Greg Wojcik, were stoic, and ready to charge. The Sharks, lined up. The crowd came crashing down around them. McAshan called the signals, the Hawaiians were ready to charge. McAshan took the snap, the teams' collided, and followed 255-pound center Richard Cheek into the end zone. As the Shark bench celebrated, McAshan looked up from the turf of the Gator Bowl, and from under the pile of Shark and Hawaiian players saw the official "touchdown" signal. Jacksonville won 21-14. The ghost of last-second losses was gone and the Sharks breathed a sigh of relief.

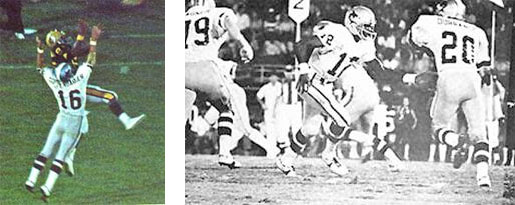

Ron Coppenbarger defends against Hawaii, Reggie Oliver hands off to Tommy Durrance

Jacksonville was 2-3, and still feeling the effects of their come-from-behind victory over Hawaii, as they traveled south to face in-state rivals the Florida Blazers in Orlando. The Sharks coaching staff learned that Eddie McAshan, hero of the Hawaii game, would not be able to play against Florida due re-injuring his shoulder. Off the field, the Blazers, only five games into the season, were already reportedly looking for another home. Dismal crowds at the Tangerine Bowl (about 12,000 a game) were prompting management to look to Tampa, Florida and Atlanta, Georgia for possible "home" games.

An incredible crowd of 23,890 packed the Tangerine Bowl as the two teams faced off in the first game of an in-state rivalry. The Blazers cruised out to a 31-11 lead before the Sharks raged back. Jacksonville, stumbling through three quarters, benched quarterback Kay Stephenson after two quick interceptions, and sent in rookie Reggie Oliver. Oliver was then replaced by veteran John Stofa, but returned to the game when Stofa was ineffective. He ignited the Sharks. Oliver scored on a 10-yard touchdown run early in the fourth quarter to cut the Blazer lead to 31-19. Moments later, Blazers' Erne Calloway and John Ricca blew in and sacked Oliver for a safety and a 33-19 Florida lead. The Sharks came back. Oliver hit Tom Whittier on a 6-yard touchdown pass that made the score 33-26 with just 2:23 left in the game. This time the Blazer defense held. Larry Ely, who had 10 tackles and 2 sacks, led the hard-hitting Blazers. Jacksonville scrambled, trying desperately to fight back. As the final gun sounded, Oliver hit Tom Whittier with a long pass down to the Blazer 30, but it was too little to late.

"If we'd had 30 more seconds, I think we would have won the game," said coach Bud Asher, referring to the Oliver-to-Whittier pass as the final gun sounded. The coach praised his rookie quarterback Reggie Oliver, who directed the desperation march. The Sharks fell to 2-4.

During the week, Sharks owner Fran Monaco decided to make a move. Monaco, concerned over the play of his team, fired old-time friend and head coach Bud Asher. The team was shocked. Monaco told the media that the team "needs a change" and that Asher had lost too many games at the last minute. The Sharks and the WFL were a risky investment, and nothing filled the house more than a winning football team. Asher was the first-ever head coach to be fired in the WFL.

Owner Fran Monaco named Charlie Tate the new coach of the Jacksonville Sharks.

The Jacksonville Sharks faced what was perhaps their biggest challenge of the WFL season- the undefeated Birmingham Americans. " Birmingham's offense is awesome. They have two good quarterbacks in George Mira and Matthew Reed, and Paul Robinson is a great running back," said coach Charlie Tate. The Americans had the top offensive team in the WFL, averaging over 360 yards a game. The Sharks would counter with Tommy Durrance, the WFL rushing leader with 443 yards on 123 carries, and Shark cornerback Alvin Wyatt who was rated second in the WFL with 4 interceptions.

27,140 Jacksonville fans welcomed new head coach Charlie Tate and the Birmingham Americans to the Gator Bowl. The Americans, leading the WFL with a perfect 6-0 record, featured "The Matador" George Mira at quarterback. Mira, a 10-year veteran had led the Americans to several wins in their maiden season. Mira's understudy, Matthew Reed, was earning a reputation as the best reliever in the WFL. When Mira was injured or faltered, Reed was always ready to come in. Reed had directed the Americans to two wins (both over Detroit) in the final minutes. From the opening kickoff the Sharks fought Birmingham tooth-and-nail. Neither team could establish a running game and that left quarterbacks Reggie Oliver and George Mira dueling for supremacy. Late in the first quarter, Shark kicker Grant Guthrie booted a 31-yard field goal, giving the Sharks a early 3-0 lead.

In the third quarter, Grant Guthrie kicked a 51-yard field goal for a 6-0 Sharks lead. In the fourth quarter both teams began to move the ball and the game started. Quarterback George Mira was injured on a blitz by Jacksonville, and American coach Jack Gotta sent in rookie Matthew Reed. Reed wasted no time turning around the Birmingham fortunes. Driving the Americans with precision passing and running, Reed drove the Americans through Shark territory. At the Jacksonville 27, Reed hit receiver Alfred Jenkins for a touchdown and a 7-6 lead. The Sharks struck back. Rookie Reggie Oliver, from Name Marshall Name College, marched the Sharks down field, 88 yards, to the Birmingham 5. With 1:09 left in the game, running back Tommy Durrance swept right, avoided a rush of Birmingham defenders and dove into the end zone. The 27,000 fans leapt to their feet, Fran Monaco let out a scream on the sidelines and Jacksonville led 14-7.

The Jacksonville faithful had seen this before. Final minutes, Sharks leading, opposing team with the ball, the ghost of defeat was coming back to haunt them again. American Jimmy Edwards gathered in the kickoff and ran straight up field, broke a tackle, found an alley in the Sharks' return coverage, and nearly ran the kickoff back for a touchdown- he was caught from behind at the Jacksonville 47 admist gasps from the Shark sideline. Matthew Reed, calm and alert, gathered the Americans around him and began to get the ball down field.

On the first play of the drive, Reed took the snap, dropped back and threw a screen pass to Paul Robinson who turned up field and ran for 11 yards to the Jacksonville 36. Reed than faded back and hit Denny Duron, in coverage, over the middle at the Jacksonville 25. The crowd was going insane. Charlie Tate screamed at his defense to hold the Americans. Birmingham broke the huddle, lined up against the Sharks, and Reed dropped back. The Sharks came with an all-out blitz, and Reed barely got a pass off to Jim Bishop before Ike Lassiter came barreling in on him. Bishop made the catch and rumbled down to the Jacksonville 6 yard line. Reed then ran the ball four yards to the Jacksonville 2. After Reed's run, the Americans were starring straight ahead at the end zone, with the ball lying at the Shark two yard line.

The scene was the same, the coaches were different. New Sharks coach Charlie Tate wiped the sweat off his brow, clinched his teeth and now prayed for his defense to hold. Matthew Reed handed off to Charlie Harraway, who followed offensive lineman Joe O'Donnell, and smashed into the end zone for a 14-14 tie. A silence fell over the Gator Bowl, as the ghost of defeat rattled its' heavy chains. The Shark sideline was expressionless, the tension deafening and the Americans lined up for the game-deciding "action point".

Head Coach Jack Gotta called Reed's number, "Rollout right to pass or run". Matthew Reed called the play in the huddle and came to the line. It all came down to one play. Birmingham, undefeated at 6-0, was experienced in late victories, Jacksonville (2-4) had tried to beat off the ghost of last second losses that haunted them in the young WFL season. Reed called the signals, took the snap, and ran right... suddenly, Reed made a cut to the middle of the field that left the Shark defenders moving away from him and rumbled up the middle and into the end zone for the win. Birmingham defeated Jacksonville 15-14, the Americans were 7-0 and Jacksonville fell to 2-5.

At 2-5, the Sharks gathered together to continue to improve the team. The Sharks headed to Honolulu for a game against the Hawaiians. Shark coach Charlie Tate and his assistants worked all week studying film and shoring up the holes in the Shark defense. Tate also worked on getting his young quarterback Reggie Oliver ready in case starter Kay Stephenson was in trouble. Tate also decided to work in a new offensive system into the Sharks playbook called the "Veer". The "Veer" offense features blocking assignments so that either a linebacker or cornerback is not blocked by offensive linemen. That leaves the quarterback with three options when he comes down the line of scrimmage, and also allows for better downfield blocking. "The best thing about the veer," said Shark coach Charlie Tate, "Is that you don't need as many outstanding backs to run it with." Tate did have two outstanding young quarterbacks in Eddie McAshan and Reggie Oliver, and the running of Tommy Durrance was certainly making the offense a threat.

Jeff Davis runs for the Sharks

At Honolulu Stadium a small crowd gathered under the South Pacific sunshine. On a day that was more likely to be spent lying on a black sand beach or surfing the blue-green waves, 10,000 football fans sat scattered around the old stadium nicknamed "the Termite Bowl" by local media. Jacksonville and Hawaii didn't do much to convince the fans they made the right choice, putting down $8 for a game ticket. In a defensive battle, the only score of the first quarter came on the first series of downs. Shark rookie quarterback Reggie Oliver threw a 46-yard bomb to Edgar Scott, who blew by Hawaiians Dave Atkinson and Hal Stringert for a 7-0 lead. Then the defenses took over. Neither team could drive the ball down field as the game was dominated by Hawaii's and Jacksonville's front lines.

With 2:44 left in the half, newly acquired quarterback Edd Hargett hit John Kelsey for a touchdown and Hawaii converted on the action point to make it 8-7 Hawaiians. The score stayed that way until there was only 2:14 left in the fourth quarter.

The winning touchdown came after the Sharks took over following a punt on the Hawaiians 48. On third-and-long, Reggie Oliver, about to be sacked scrambled for 10 yards and a first down. On a second-down play Oliver found Edgar Scott wide open over the middle but Scott dropped the ball. Oliver came right back with the same play and hit former Oakland Raider Drew Buie for the touchdown and a 14-8 Jacksonville win.

"Given time I knew we could throw on 'em," said coach new Shark Charlie Tate who received the game ball, "in fact I probably should've had us throwing more on them." Tate also added, "I know how it feels to lose a heartbreaker, we've lost a few ourselves this season." Tate also praised cornerbacks Mike Townsend and Solomon Brannan who both intercepted two passes each to end Hawaiian drives.

The Sharks were 3-5, and starting to believe in themselves. Overall, the Sharks lost a total of six games by only a total of 25 points (for an average of 4.25 points a game), the Sharks also lost four games in the final minutes of play. Shark coach Charlie Tate had his team improving. The Sharks, under Tate, had a 1-1 won-lost record. Tate and his staff were preparing for the mighty Memphis Southmen who were coming to the Gator Bowl.

September 2, 1974, the Southmen traveled to Jacksonville, Florida. The Southmen, 6-2, were coming off a 26-18 win over the Florida Blazers and featured skilled players such as quarterback John Huarte, running backs JJ Jennings and Willie Spencer, and a tenacious defense. The Sharks defense, led by Glen Gaspard (73 tackles), Ron Coppenbarger (53 tackles) and Fred Abbott and Bob Taterak (39 tackles each) would have their work cut out for them. The Sharks' offense was led by Tommy Durrance who had rushed for 509 yards for the season.

22,169 Shark fans watched Jacksonville play Memphis like champions on every down. With Memphis leading 8-6, Shark running back Tommy Durrance rumbled into the end zone for a 13-8 Shark lead. Yet again, the defense, which had played well for three quarters, would be asked to hold a late lead. The Southmen, one of the more powerful teams in the WFL, began their march. Quarterback John Huarte, an experienced former NFL quarterback, brought Memphis back with short passes and handing off to Willie Spencer. Spencer ran through the Sharks defense en route to a 100-yard game and the Southmen rallied back from their second deficit, and Spencer dove for the winning score to make it final: Memphis 16, Jacksonville 13.

The ghost was back in Jacksonville. The coaching staff beside themselves on how to stop the late losses the team was experiencing. Charlie Tate realized the Memphis game seemed to take some of the fight out of his team. Jacksonville was 3-6, and in need of a win. Coach Tate told reporters, "We're just inches away from putting it all together. We fought right down to the wire in every game...we've just been unfortunate."

Off the field, the Shark players were also dealing with another type of challenge: no pay. The players hadn't received paychecks since the game with the Hawaiians and tensions were running high. Many players had families to support, and bills to pay, and needed to get the money that was promised to them. Owner Fran Monaco assured the team that the problem was only "temporary" and that adequate arrangements would be made to make up the missing pay. Also, many reports circulated around Jacksonville regarding the dwindling attendance at the Gator Bowl. The Sharks last two home games had drawn 27,000 and 22,000- not bad by WFL standards, but apparently not good enough to allow the team to meet its financial obligations.

On September 5, 1974 the Sharks hosted the Philadelphia Bell in an important Eastern Division meeting. The Bell came into the game at 4-5, while Jacksonville was 3-6. A win would allow the Sharks to gain some ground on Philly while still putting them in good shape for a possible playoff spot. The Sharks lost the services of strong safety Ron Coppenbarger to a knee injury.

In the pouring rain, 17,851 fans, witnessed an aerial circus that was staged not by the infamous "King" Corcoran of the Bell, but none other than Name Marshall Name University rookie quarterback Reggie Oliver. Oliver completed 14 of 26 for 321 yards and 2 touchdowns as the Sharks defeated Philadelphia 34-30. Tommy Durrance also found the form that made him a leading rusher in the WFL, running for 72 yards and two touchdowns.

After the game, a jubilant Oliver shared the credit was his offensive line, "I wasn't sacked once. Our offensive line gave me the best protection of the year and blocked so well for our running game that the passes opened up." The Sharks were 4-6 and about to face their most difficult time of the WFL season in the next month.

With a 4-6 won-lost record at the midway point of the season the Sharks were starting to develop some problems off the field. It was confirmed that of the 105,000 fans that attended the team's first two home games over 44,000 received free tickets- lowering the average attendance from 52,946 to 30,946 and bringing into question the teams' credibility. Attendance shrunk from a average of over 30,000 to crowds of 20,000, then down to 17,000 at their latest home game. Fran Monaco had hit a wall financially. If there was to be a team in Jacksonville, an investor would have to step in and bail out the club. Monaco told WFL officials that he would surrender the franchise unless financial assistance came from another source. The Sharks had reportedly lost $500,000.

Three prospective groups stepped forward in an attempt to purchase the WFL Jacksonville franchise. A Chicago group represented by no other than ex-Bear great Dick Butkus, a long-time friend of Shark owner Fran Monaco, came to town with a $375,000 certified check. The WFL told him it wanted at least $100,000 more in advance. Another offer came from Florida businessman Wayne Pease and another group headed by Miami contractor Matson O'Neal, who claimed he owned the rights for an option to buy the team. As the WFL and Monaco worked out the details with the three ownership groups, the Sharks boarded a charter flight to Philadelphia for a rematch against the Bell. The players hadn't received paychecks for three weeks.

The WFL celebrated the kickoff of the second half of the season, and the Sharks faced the infamous "King and His Court" for a second time. "King" Corcoran had passed for 1,971 yards, while completing 154 of 291 attempts for 18 touchdowns. Running back John Land had been a consistent performer all season, and with the addition of linebackers Tim Rossovich and John Sodaski the defense was also playing better.

In Philadelphia, the Sharks walked out onto the field at JFK Stadium. The 100,000 seat facility, which had seen many historic games, rose high above the players. The yellow glow of the lighting towers made it impossible to see clearly up to the top row of the stadium and at game time, 7,230 fans were lost among the thousands of seats.

The Bell fans sat through a four-hour "slugfest" between two desperate teams. The Sharks, aided by two Grant Guthrie field goals held a 6-0 halftime lead. In the Bell locker room, Coach Ron Waller made several offensive adjustments and the Bell came out "on fire". Philadelphia erupted for 22 points as "King" Corcoran passed 74 yards to John Land, kick return specialist Ron Mabra returned a punt 86 yards for a touchdown and Claude Watts added another score to make it 15-6 Philadelphia. In the fourth quarter, the Sharks, led by Reggie Oliver, came back on a drive that ended with Oliver hitting Dennis Hughes for a 16-yard touchdown and a 22-22 tie. As regulation play ended the two teams awaited the overtime period. In the WFL, overtime didn't end with the first score. The teams would play through an entire overtime period.

The Bell scored first on a 26-yard field goal by Dennis Torzala. Torzala had actually missed four field goal attempts in regulation but nailed the kick over a diving Mike Townsend of the Sharks. Philadelphia then drove 58-yards on eight plays, and Claude Watts scored from the three to make it 33-22. On the Sharks first series, Reggie Oliver threw an interception to linebacker John Sodaski, who ran for 22 yards and a touchdown and Philadelphia won, stunning the Sharks, 41-22.

On the charter flight back to Florida the Shark players and owner Fran Monaco had reasons to be optimistic. Despite the loss, and a 4-7 record, the Jacksonville players breathed a sigh of relief. On the plane was New York investment banker William Pease carrying a check for $2.5 million to be deposited into the teams' account? The Sharks had found their financial savior and the team would remain in Florida.

William Pease, of the stock brokerage firm of Pease & Ellison had come to the rescue of the Sharks' owner Fran Monaco, who warned he may have to move the team to another city unless he received financial backing. Monaco revealed he was carrying the team with his own personal funds for over a month and told reporters that it would take between $4.5 million and $5 million to purchase the Sharks. In May of 1973, Fran Monaco paid $450,000 for the WFL franchise. Pease and Monaco were still working out details of the transaction (whether it was a loan or an offer for the club) as the 4-7 Sharks prepared to host the Portland Storm.

The Portland Storm came to Florida a much different team from when they started the WFL season. Portland came into the game at 1-9-1, but under head coach Dick Coury was playing more competitively. The recent addition of quarterback Pete Beathard also helped to turn things around in the Northwest. After talking the lead with 1:08 left to play against the Storm, the Shark defense allowed Portland to move the ball at will and set up a 28-yard Booth Lusteg field goal for a 19-17 win. In a deafly quiet Shark locker room quarterback Kay Stephenson said, "I've been on a lot of clubs, and I've never seen things happen like they have to this one." Stephenson drove the Sharks to two touchdowns in the fourth quarter and a 17-16 lead. Portland quarterback Pete Beathard, a new arrival from the NFL, called on 11 years of pro experience and put the Storm in position for Lusteg's field goal as time ran out. It was Portland's third victory. Jacksonville, which sunk to 4-8, and didn't receive paychecks for the fourth straight week.

General Manger Fran Monaco, who sold controlling interest in the team to William Pease, said arrangements had been made to pay the players all their back pay. Defensive end Ike Lassiter said the money problem is nothing compared to the frustration over the fact six of their losses have come in the last minute or two. "I'd play for nothing if we could just win," Lassiter said. "Our spirit is good. The guys play together. Maybe we just need a few breaks."

Coach Charlie Tate shook his head and said, "I didn't believe it could happen again. Our defense didn't play cohesively on their last drive, but I didn't believe Portland could score. We did all we could on the pass to Joe Wylie that set up the field goal. We tried to keep him contained in bounds, but he got out and stopped the clock."

Off the field, negotiations between Monaco and Pease continued. Monaco had told reporters that Pease was purchasing the team for $1.5 million. As the deal stalled, and promises of paydays passed, the players became despondent with the situation. Many had families, house payments, car payments, and various bills that needed to be paid- and the Shark players hadn't seen a full payday for six weeks. Amid the financial ruin that seemed to immanent, the Shark players made a stand. Many of the Sharks were rooming together to save on money, and many of the players who had families had sent their wives and children home. In a letter to WFL commissioner Gary Davidson, the players told the WFL commissioner they would not travel to California to play the Sun unless they received their back pay. They also threatened to "picket" the game outside Anaheim Stadium. After talking to Gary Davidson the team went to California with his personal promise of payday and that other potential investors were being interviewed. Sharks quarterback Kim Hammond said, "I spoke with Gary Davidson by long distance and he has shown that he has a personal interest in our players. We have renewed confidence in the WFL now that we feel we have resolved some of the major problems and got some of the assurances we wanted. Gary didn't tell me who the potential owners were, I'm optimistic about the situation getting settled soon."

On September 22, 1974, the Sharks climb to chaos reached the pinnacle. The WFL reported that it was repossessing the Jacksonville franchise and that former owner Fran Monaco and potential owner William Pease would be thrown out of the league. The media reported that William Pease, a wealthy New York financier, was bound over to Superior Court in Hartford, Connecticut on five counts of grand larceny. He also faced 15 counts pending against him for practicing real estate without a license. The 15 counts represent 55 parcels of land in Connecticut worth $1.5 million. A complaint was also lodged against him by two business associates that claimed he swindled $37,000 from them. "As far as the WFL is concerned," league commissioner Gary Davidson said, "there's is not now nor has there been any relationship between us and William Pease. He has no equity or ownership position at all in our Jacksonville franchise."

WFL official Jim Chitwood told the media the Jacksonville players would receive their back pay from league funds. "This is pretty shocking", said Chitwood. "I mean, just look back to three weeks or a month ago and all of us figured we were in good shape. We thought everything was fine. Mr. Monaco has decided not to make any statements at this time but as I understand it the club will be repossessed over the weekend." With the attendance problems (average attendance had slipped to roughly 17,000 a game), the Sharks players hadn't been paid in weeks and finally realized that they wouldn't be (paid) for a while. Reserve quarterback Kim Hammond, a practicing lawyer, began representing the players and starting litigation against the team.

On the field, the financial problems of the Sharks came crashing in around the team. In Anaheim, the Southern California Sun rolled up a 46-0 half time lead, and then coasted to a 57-7 win. The Sharks were as flat as the Sun was sharp. With Southern California knocking on the door of a 64-0 lead, the Sharks recovered a fumble and Reggie Oliver drove the team on a 9-play, 93 yard touchdown march in an attempt to save the club complete embarrassment. In the locker room, a dejected Charlie Tate told reporters, "We were embarrassed. We stood around and did nothing. I saw no indication from out players before the game that something like this would happen." The Jacksonville Sharks fell to 4-9 and received one "game check" (about $150 per player) for the trip to California.

The Jacksonville Sharks would play their last WFL game in Memphis, Tennessee against the Southmen. Frustrated with a three-game losing streak, the financial mismanagement of the team, missed paydays, and a league that seemed to care less about their plight, the Sharks lost to Memphis 47-19. When the team returned home to Jacksonville, Florida, time had run out. The WFL had been assessing the remaining franchises fees to keep the Detroit Wheels and the Sharks afloat until other investor could be found. None materialized.

The World Football League didn't want to lose the Jacksonville franchise. The weather in Jacksonville was good, the stadium was great for football and the Sharks were second in league attendance- around 32,000. Sharks' officials so poorly managed the clubs' finances that the team had no cash for its survival. Many owners endorsed the idea of the Florida Blazers and Jacksonville merging, but Blazer officials, namely Rommie Loudd, were against the idea. The Sharks "savior" William Pease had fallen from grace and with his departing Fran Monaco filed for bankruptcy protection, claiming over $1.8 million in debts. The IRS filed a lien against the Sharks in Name Volusia Type County for $105,551 for social security and payroll with holding taxes from July, August and September. Despite the fact that the Sharks were defunct, the lien was filed because the team is still a member of the WFL and league officials are trying to secure investors for the club.

On Tuesday, October 8, 1974, the WFL finally closed the book on the Jacksonville Sharks. League officials sent notice that the team would "suspend operations effective immediately". The news reached the Sharks players through head coach Charlie Tate in a team meeting. In the locker room, some 50-odd players cursed, threw bitter accusations at the WFL and packed up their equipment. The scene was like a funeral, and the Sharks black jerseys fit in perfectly. Coach Charlie Tate held hope that the team could be saved at the last minute, but his hopes were fading with each player walking out the door. "The league doesn't want to dissolve us," claimed Tate. "I firmly believe that. We've got to sit tight. Hopefully, something good will happen... we have a chance."

The Sharks players had plenty to say about the situation and the WFL. Kicking specialist Grant Guthrie said in anger, "We want something to happen but right now I don't give a damn. As far as I'm concerned, the WFL commissioner (Gary Davidson) told bald-faced lies to me and about 20 other players "

"It's really a shabby situation," said back-up quarterback Kim Hammond, a practicing attorney in Daytona Beach. "The league owes us $250,000 in back pay. We've had one payday in the last 1 ½ months. We've been assured of getting paid before every game, but nothing has come. It's all been very difficult on the players and they've had to go through some hardships. Now they've reached the limit and I attribute it as the fault of the WFL. Gary Davidson and his group of merry men know they have an obligation to the players and they have the chance now to get the players sold and get this whole thing over with." Hammond also received word that the league had vetoed several potential investors in the club, including Miami contractor Matson O'Neal.

"I was willing to put $100,000 a week into the club," confirmed O'Neal, a friend of Coach Charlie Tate, "We would have taken over the obligation of the club, but I wanted to be reimbursed if I decided not to buy the club. After all, I'm a businessman first and a sports fan second".

Kim Hammond said the WFL's rejection of O'Neal as the potential owner irritated the Sharks. "He (O'Neal) came up here and met the leagues' man (WFL official Chuck Rohe, temporary Jacksonville manager). He said he was prepared to come up with the money for the Blazers' game (postponed on Monday) and returned to Miami with the understanding further meetings would be held. But no one showed up on Sunday and then nobody showed up the Monday. Apparently, what they (the WFL) wanted to do was stick him (O'Neal) with the debts of the Detroit Wheels too. That's ridiculous. I have trouble believing someone can sleep with this kind of attitude. They keep telling us we'll get our money but no money shows up. This could drag on for weeks. It's like us football players are something subhuman."

Most Shark players believed the league was ducking its obligations to their team and perhaps the Detroit club.

"If you can't believe the commissioner," said Hammond, "it kind of destroys his credibility. I've worked for weeks trying to temper the situation. When we got four paychecks behind, the guys became completely dominated by this thing. They worried about making car payments, getting behind on house payments, buying groceries. The players began to realize they may never get their money in their position. And now they have to sue for their money."

Grant Guthrie added, "I can't understand the league's highly selective attitude towards potential buyers. The league is really in no position to make demands. It owed some courtesy towards the players and so far has not shown it."

While the Sharks were disassembled, Jacksonville Mayor Hans Tanzler told local newspapers, "The situation is a disgrace. I just wish the league had done a better job of checking on its owners. The WFL let someone come in here and run a franchise who could only handle the team for about five or six home games."

Kicker Grant Guthrie said, "We want something to happen. If I go somewhere else I want to go right now. This has hurt my family enough already. Sorry to hear we have another 48 hours. This thing is affecting the lives of 70 people and I think it stinks. I've been loyal long enough. If I can get into the NFL I'm going."

The Shark players threw their belongings into duffle bags and anything else they had. Many players made plans to meet at a local tavern for one get-together. As a eerie silence fell over the locker room, the death toll sounded for the Sharks. Kim Hammonds' final comment was, "Until Davidson clears this up, I don't think he has any credibility at all. We haven't been dealt with truthfully. To say that he has lied to us would be a strong statement. But that's pretty close to it."

| Starting Lineup | |||

| QB | Reggie Oliver/Kay Stephenson* | S | Ron Coppenbarger |

| RB | Tommy Durrance | S | Mike Townsend |

| RB | Rick Lake | CB | Alvin Wyatt |

| TE | Dennis Hughes | CB | Jeff Davis |

| WR | Drew Buie | LE | Ike Lassiter |

| WR | Edgar Scott | LT | Ben Tatarek |

| C | Mike Creaney | RE | Art May |

| RG | Richard Cheek | RT | Russ Melby |

| RT | Eddie Foster | LLB | Fred Abbott |

| LG | Larry Gagner | MLB | Glen Gaspard |

| LT | Frank Cornish | RLB | Claude Simonton |

| K | Grant Guthrie | P | Duane Carroll |

| Statistics - Passing | ||||||

| NAME | ATT | CMP | YDS | TD | INT | PCT |

| Reggie Oliver | 198 | 101 | 1415 | 7 | 12 | 51.0 |

| Kay Stephenson | 149 | 68 | 815 | 4 | 11 | 45.6 |

| Eddie McAshan | 14 | 5 | 88 | 0 | 0 | 35.7 |

| John Stofa | 5 | 2 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 40.0 |

| Statistics - Rushing | ||||

| NAME | NO | YDS | TD | AVG |

| Tommy Durrance | 218 | 658 | 5 | 3.0 |

| Rick Lake | 91 | 335 | 3 | 3.0 |

| Jeff Davis | 38 | 148 | 0 | 3.7 |

| Alfred Haywood | 20 | 111 | 2 | 5.6 |

| Reggie Oliver | 42 | 107 | 3 | 3.9 |

| Wayne Jones | 28 | 90 | 0 | 2.6 |

| Ron Lamb | 33 | 74 | 0 | 3.2 |

| Edgar Scott | 19 | 73 | 0 | 2.2 |

| Eddie McAshan | 11 | 52 | 1 | 3.8 |

| Jeff Smith | 10 | 21 | 0 | 2.1 |

| Statistics - Receiving | ||||

| NAME | NO | YDS | TD | AVG |

| Dennis Hughes | 31 | 498 | 2 | 16.1 |

| Drew Buie | 29 | 421 | 2 | 14.5 |

| Edgar Scott | 27 | 469 | 2 | 17.4 |

| Tom Whittier | 18 | 297 | 2 | 16.5 |

| Tommy Durrance | 12 | 105 | 0 | 8.8 |

| Name Rick Name Lake | 10 | 75 | 0 | 7.5 |

| Jeff Davis | 9 | 84 | 0 | 9.3 |

| Ron Lamb | 8 | 36 | 0 | 4.5 |

| Wayne Jones | 7 | 61 | 0 | 8.7 |

| Alfred Haywood | 7 | 35 | 0 | 5.0 |

| Keith Krepfle | 6 | 80 | 0 | 13.3 |

| Tony Lomax | 5 | 61 | 1 | 12.2 |

| Statistics - Kickoff Returns | ||||

| NAME | ATT | YDS | TD | AVG |

| Alvin Wyatt | 28 | 596 | 0 | 21.29 |

| John Osbourne | 20 | 421 | 0 | 21.05 |

| Bubba Thornton | 4 | 95 | 0 | 23.75 |

| Ron Lamb | 4 | 69 | 0 | 17.25 |

| Carl Swierc | 3 | 68 | 0 | 22.67 |

| Statistics - Punt Returns | ||||

| NAME | ATT | YDS | TD | AVG |

| Alvin Wyatt | 33 | 197 | 1 | 5.97 |

| Solomon Brannan | 1 | 42 | 0 | 42.00 |

| Art May | 1 | 15 | 0 | 15.00 |

| John Osborne | 2 | 15 | 0 | 7.50 |

| Carl Swierc | 2 | 15 | 0 | 7.50 |

| Statistics - Punting | |||

| NAME | ATT | YDS | AVG |

| Duane Carrell | 93 | 3819 | 41.06 |

| Statistics - Interceptions | ||||

| NAME | NO | YDS | TD | AVG |

| Alvin Wyatt | 5 | 8 | 0 | 1.6 |

| Mike Townsend | 4 | 20 | 0 | 5.0 |

| Solomon Brannan | 2 | 39 | 0 | 19.5 |

| Ron Coppenbarger | 2 | 16 | 0 | 8.0 |

| Jeff Davis | 1 | 12 | 0 | 12.0 |

| Glen Gaspard | 1 | 9 | 0 | 9.0 |

| Rich Thomann | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

NOTE: The 1974 Jacksonville Sharks team page was researched and written by Jim Cusano. This page appeared on the former World Football League Hall of Fame Website and is used with permission.

© Copyright 1996-2007 Robert Phillips, All Rights Reserved