-

WFL

-

1974 Season

-

1975 Season

-

Multimedia

WFL Interviews

The World Football League Website is proud to presents an interview with the 1975 WFL President Chris Hemmeter

HOF: In 1973, Gary Davidson announced the formation of the World Football League. When did you become involved in the WFL and the ownership picture in Hawaii?

CH: A gentleman, I think from California, was holding the franchise and he was one of the original promoters, and Gary let us know that we could acquire the franchise for a relatively modest sum of money. The first meetings were setup in late '73. We were at he Newport Beach law offices; there was a group of us, maybe ten to fifteen people and they made a presentation about the league and what they were trying to accomplish and how they were going to capitalize on various aspects in the game itself and how it was going to be promoted. The timing was unique due to various problems within the NFL and made a good case for the league.

HOF: Did establishing a professional football franchise in Hawaii pose any unique challenges to the ownership group?

CH: Getting the franchise was certainly not a problem, and I think that was the main problem of the World Football League. There wasn't a great deal of discipline regarding the handling and administration of the franchises and their purchase, we able to acquire the franchise and then raise the equity within the community. We secured the stadium lease, and we had a good relationship with the local governments.

There was always the problem of having to move five hours off the west coast of the United States. That wasn't a problem for the teams in California and Portland, but if you are coming from Orlando, Chicago or New York, there was some expense and jetlag to deal with. So, that was a factor, but I think Hawaii added some glamour and notoriety to the WFL.

HOF: What was your first impression of Gary Davidson?

CH: I thought Gary Davidson was a very nice gentleman. He had personal experience in setting up new leagues, his credentials were excellent, and he was very charismatic and made a wonderful presentation. We were excited and the community was very supportive of the Hawaii franchise. The local government, politicians, the governor, the private businessmen in Hawaii all showed a lot of support for our venture. It was an excellent experience, and I thought Gary, after my first number of meetings with him, was very experienced in handling the World Football League. History would probably show that his only shortcomings were the fact that he wasn't disciplined enough in selling the franchises and setting up the business aspects of the league. It was more of a promotional deal where he was selling the WFL franchises to anyone who had a couple of dollars and a lot of promises.

HOF: Hawaii signed Calvin Hill, Randy Johnson, Vince Clements, and Ted Kwalick to WFL contracts. Was the franchise so successful in signing NFL talent?

CH: I think it went back to our head coach, Mike Giddings. He was an experienced football guy, and he had connections in the NFL. Of course, the glamour of playing in Hawaii, the excitement the centered around the WFL and the arrival of Larry Csonka, Jim Kiick and Paul Warfield created a lot of attention. Many of these players saw the WFL as an opportunity to finish their careers, or extend their careers, while trying to have a part in establishing a new league.

HOF: What was the mood in Hawaii for the home opener against the Detroit Wheels?

CH: Tremendous euphoria. We were inexperienced owners of professional sports teams. The league itself was trying to feel its way through some of problems that existed but there was a sense that we had come upon a need and we were trying to fulfill that need. The WFL offered a broader form of entertainment, in some prime markets and in some secondary markets, and it extended the football season. So there was a lot of euphoria, although I think it was naive euphoria.

HOF: The Hawaiians, on a per capita basis, out drew many of the WFL teams, however the original attendance was low. Did that concern the ownership group?

CH: We were a bit concerned. Hawaii is no different than any other city. They support winners. The University of Hawaii, whether it be their baseball, football or basketball programs drew well when they were winning, the attendance was very strong. So we felt that if we could advance our organization and start winning some ball games, with some of the incredible talent we had on that team, that we would be able to draw the people to the games. We also had a very aggressive sales and marketing program at that time.

HOF: When the first signs of financial trouble surfaced in the WFL, what was the mood amongst the ownership groups?

CH: There was a lot of tension. Owners starting looking at the league as being essentially made up of three or four key players and a number of 'hanger-on's' that were there due to some pretty high-flying promotions. The approach that was taken by the home office in selling and establishing some of the teams and not having the business discipline that went along with the program. There was a sense of fear. You quickly learned that when you are dealing with a league that you are only as strong as the weakest teams in the league. As a result of that, the WFL began to spiral down very quickly as some of the weaker franchises started to have serious problems to the extent that there was question as to whether they would be playing from week to week.

HOF: Who were some of the key players in the World Football league?

CH: John Basset was excellent. John was one of the key players. I think that many of the owners in the World Football League looked up to John due to his fielding of a first class operation and having the level of optimism he had. Another was John Bosacco in Philadelphia. Tom Origer in Chicago. Sam Battistone in Southern California. That was the core group in the WFL.

HOF: In October, 1974, Chicago Fire owner Tom Origer called an emergency meeting of WFL owners. At this meeting Origer threatened to withdrawal the Fire from the league unless Davidson resigned. Where you present at the Chicago meeting?

CH: Actually, I do remember being at the Chicago meeting, there was a lot of tension at the time. Some of the teams were getting ready to fold (Detroit and Jacksonville) or move (New York and Houston) and many were talking about not showing up for games due to financial concerns, or, better stated, a lack of finances. In retrospect, it was the appropriate thing to do, be present. Many of the owners supported Gary's resignation some did not.

HOF: Many of the league owners disliked the WFL business plan that called for the stronger franchises to pay the debts of the weaker teams to keep the league, as an entity, sound financially. What was the mood among the 'key players' regarding this imitative in the WFL?

CH: We were extremely concerned at that point in time. The weakest teams in the WFL were determining its success, or its level of success. It was a cost-benefit analysis. We had to decide if it was in our best interest to subsidize these teams to protect our investment. I think for an extended period of time we felt intimidated, or forced, that we had to invest more money to protect the money we had in. What happened is that, for those owners, a lot of the fun left the league. Everything became an economic struggle instead of an athletic event, it took a lot of bloom off the rose.

(WFLHOF note: A published article in the Chicago Tribune, claimed Fire owner Tom Origer told reporters that he had paid $60,000 to the WFL for his league assessment and an additional $40,000 for his share of the debts of Detroit and Jacksonville. Origer claimed, "That's $100,000 that went out of my club. I'll run my team, it's my business, and I'll decide when it isn't worth it. Let the other owners be responsible for their teams.")

HOF: Was there discussion amongst the owners to eliminate those teams? Or was there fear of the media backlash?

CH: There was a lot of discussion about that. There was discussion of pulling the league down to five or six ball clubs, but the problem with that is when you start to abandon your original business plan and lose your confidence in the fan support, things can spiral down quickly.

We knew that we were dealing with the problem of having to establish ourselves in the shadow of the powerful National Football League, but we were also having to defend our positions, the weaker teams in the WFL, and why were weren't moving forward in the manner that we had planned. It was classic business collapse. It stemmed from the high-flying promotions that were the birth of the league. 'High-Flying' promotions meaning the great celebrations and fabulous cocktail parties that occurred when another franchisee was brought on board. No one took the time to do the background checks to see if this new owner had the staying power to stay in the WFL, and the 'star syndrome' carried many of them away.

The 'star syndrome' began when some of the WFL owners believed that if you had two or three big stars that they would carry you to success. You could build your marketing around them and establish a sense of loyalty. The payrolls went crazy; they got in trouble, and turned to us and said, "Bail us out!" I think that can work in an established league, but we were putting the cart before the horse. We needed to establish ourselves in the communities and develop a sense of loyalty and pride. The 'star syndrome' was the single most 'cause for the failure of the WFL. The belief that these name players could 'cure all ills' was the biggest mistake.

HOF: How did you implement the Hemmeter Plan?

CH: When the WFL went into bankruptcy in 1974, we were all trying to figure out what we were going to do; let the league fold, reorganize or steal quietly away. We decided that we would take a business-like approach to professional sports and apply certain principles to minimize our fixed costs and maximize our variable costs as a percentage of total revenues. We thought, with this plan, we could go to bankruptcy court and buy back the player contracts and such and move forward. That was the plan that was ultimately called the "Hemmeter Plan". We were trying to create an environment of 80% fixed costs and eliminate the runaway payrolls of the 1974 WFL and have a profitable league based on an attendance of 14,000. We thought if we could achieve that, then we would then be able to move forward and create a sound base to build on.

The first aspect of the Hemmeter Plan was getting our payroll under control and encouraging the players to sign for a percentage of revenues as apposed to a fixed dollar amount, each player would be, in essence, a private contractor. A 1% running back may run behind a line of .75% linemen, and everyone would have an interest in the success of the team. That was the basic concept behind the plan.

HOF: Did the WFL ever consider signing college stars exclusively and not the high priced NFL superstars?

CH: I thought that if we took a more conservative, long-range approach to the WFL, and implemented a plan like the "Hemmeter Plan" that we wouldn't have run into the problems that we had in 1974. In fact, we went back and ran a business model and applied the "Hemmeter Plan" it to the dealings of the '74 WFL and proved that the business model would have let the first year league be profitable. The mere fact that you were limited to 45% of revenues for talent, meaning that you would eliminate many of your 'big name' players, led many to feel that there could be 'league players' that would be paid from a pool of league funds, much in the way that the WFL paid for advertising and promotion. For example, if the WFL targeted five NFL superstars to play in the league the WFL would pay for the salaries as an overall enhancement to the league so that the individual teams wouldn't bare the burden, or the full burden, of the payroll.

HOF: When the Stars moved to Charlotte it left the WFL with a huge void in one of the most important major markets, New York City. Before the 1975 season, Fred Ballon approached the WFL about the possibility of securing a New York franchise. Why did the WFL delay the proposed New York team?

CH: We had a meeting with the mayor of New York and the head of the Stadium Commission. We were trying to obtain the playing rights to Shea Stadium and get out of the stadium (Downing Stadium) that we were relegated to which had some serious problems. The negotiations, between the New York ownership group and the WFL, broke down due to the inability to secure a stadium in 1975. It was hard to get support from the local government due to the chaos of 1974. We (the WFL) were not welcome; they weren't excited about us playing in New York. In fact, the mayor told us, "establish yourself as a league and then come see us."

Each WFL city had a different situation. Many of the cities indicated that the stadium would be available, but the conditions they proposed were so extreme that it was impossible to have a successful business. Whether it was as straightforward as the rent, or more secondary like the electricity or the hours of operations. The NFL had a hand in making things hard for us, but that's business. We fought that specter all over the country, I was traveling throughout the country under the concept of 'righting a wrong'.

I recall my first meeting with NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle. I stated that I was hopeful that we could work together, for the benefit of the athletes, and in essence, be a training ground for the NFL, whether it is in developing players or future NFL cities. He and I talked about everything, and he was very interested in the variable cost scheme (the Hemmeter Plan) but at the time he stated, "Chris, one mistake you are making is that you are spending too much on player salaries at 45%." We talked to that at some degree. I had some people inside the NFL that provided me with some information as to the dealings the NFL was involved with against the WFL, nothing illegal, but they sure made it difficult to do business. I thought that Pete and I had a tremendous relationship but his opinion of us was that we were a footnote in history. He delegated some of the owners to keep a watchful eye on us to make sure that we didn't give birth to something substantial.

HOF: Did you feel the NFL worked with the media to discredit the WFL?

CH: Yes. They controlled the media in professional sports. They had a monopoly, and they were so strong and so powerful and had so much talent in the promotional arena that it was virtually impossible to deal with the media. The NFL would 'wine and dine' the media and anytime some one would be aggressively and helpful to us the NFL would come over and say, 'Fells, you can choose your own medicine, but unless you back away from the World Football League you can be assured the National Football League will never consider coming into your communities or even taking a look at you." That wasn't the cause of the demise of the World Football League; the demise of the World Football League took place in 1973 when Gary Davidson lined up owners who didn't have the financial reserves to make the league a success.

HOF: Did you divest from Hawaii when you were commissioner?

CH: I probably left my investment in the team. We were all good friends; Eddie Sultan, Chuck Rholes we were all close out there. Young entrepreneurs of the community, movers and shakers, we all worked hard at making the team work. It was sad to see it die, but as they say, it was better to have loved and lost then to never love at all. The WFL was, bar far, the most exciting and frustrating business venture I was ever involved with. I realized, after it was too late, that the foundation of the WFL was too weak and despite the excitement of the sports event, it was doomed to failure, it was just, so, well the potential that went unrealized. It takes a lot of time to build a sense of loyalty, and once you have that you can market the events. But you really need a sound business structure to enable that to become a reality. In the WFL, we found that many of the people involved we qualified to market the league, but didn't have the ability to support the league financially. In the WFL there was no extinction between promoter and owner, that is a dangerous partnership.

HOF: What is your opinion on the new XFL?

CH: I have a friend in the broadcast business. He feels that the XFL will be a knockout success. On Monday nights, wrestling has outdrawn the NFL for its sheer entertainment value. The XFL, unlike the WFL and USFL, isn't going to emulate the NFL. They (the XFL) are going to market the game, and encourage the drama of the sport. I've been told that they are planning all kinds of wild, high-energy types of entertainment. This will probably be a huge draw to the workingman.

The XFL, unlike the WFL and USFL, is a corporation. Using this model, they can avoid some of the problems that prior leagues have faced. Purists will say that there won't be the element of competition won't be there. I think, through incentives, they can create the competition and drama, but it will be hardcore entertainment. The games won't have predetermined outcomes, but they will dramatize the human emotions of football. You can take a smart comment and multiply it by ten, and then you have a shouting match. I can't help but think of the Harlem Globetrotters, and what they have brought to the game of basketball. The XFL will be entertainment.

HOF: Did the WFL ever consider stopping the '75 season, holding a playoff, and regrouping for the '76 season?

CH: We explored that. But once the fun left the league, and the cash flow wasn't there, the outcome was predetermined.

I can remember late in 1974, when I was with the Hawaiians, one day when I got a call from the Florida Blazers. They asked, "how are you doing out there for next week's game?" I said, "we are having great success with ticket sales, we've sold 20,000 tickets and we are expecting about 30,000 for the game!" Florida says, "geez that's really great. We were looking forward to it but I don't think we can make it out there and I just wanted to let you know." I said, "Wait a minute. I just told you we had 30,000 coming out to the stadium and now you're not coming!" He said, "that's right. But I'll tell you what…..I need two weeks payroll and I need the airfare. It will cost you $100,000,if you wire we that amount of money we'll come out for the game."

Another time I received a call from Memphis owner John Basset. There was a crisis in Detroit and Jacksonville regarding unpaid players and he told me that there was the potential of a lawsuit by the players against the owners of the WFL, a suit claiming "umbrella liability" for lost wages and that we would be responsible for those payments. That's when the luster, the glamour, wore off for many of the legitimate people in the league.

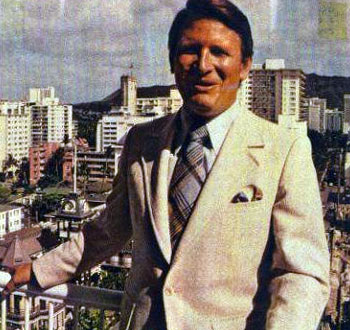

Memphis owner John Bassett and Commissioner Hemmeter

HOF: How did you feel about Memphis and Birmingham applying for franchises in the National Football League?

CH: Of course I thought they were great cities for the NFL. Both Memphis and Birmingham were great cities for us. John Basset was a sound owner, and Birmingham led the WFL in attendance. The south is incredible football country. I recall the first time I flew into Birmingham as commissioner of the league. I came down for a game, I was on United, and when the flight landed the door burst open and there were two policemen with dark glasses, helmets and weapons on their side who entered the plane and told everyone to be seated. They came over to me and said, "Mr. Hemmeter?" I was thinking to myself, "What in the world is going on? The policemen answered, "We're here to escort you downtown." I said, "You don't have to do this." They replied, "we do this for high school teams!" They escorted me downtown to my hotel. When I went out to dinner I had a police escort.

In 1974, we had everything going for us, the timing was right. If we had put together ownership groups with capitalization requirements that '74 season could have been a springboard for a second alternative to the NFL. I think that the leagues would have merged after a certain amount of time. Unfortunately, the WFL never materialized the capitalization factors that were needed to succeed. The '75 season was really "dead on arrival", the damage had been done. I think we proved that there was a demand for a 'secondary market' in professional football. The college ranks had talented players that weren't being absorbed into the NFL, and you could develop a quality product. I also think that the concept of 'the weakest link in a chain determining the strength of that chain was never more apparent than in the WFL. No group or league should ever move forward unless they have a commonality in their financial structure and their goals 'cause that can be disastrous. So, there is a level of negativity associated with the World Football League, it had incredible potential but it lacked a sound business plan. The WFL should serve as a beacon that a league is no stronger than its weakest franchise, and if you are trying to 'right a wrong' you will need time and patience to win the loyalty and support of the community.

HOF: Colored Pants?

CH: O.J. Simpson was of tremendous help to me in 1975. He was one of the key operatives who gave me information on the NFL, as did Carol Rosenbloom and Al Davis. Carol and Al both wanted franchises in the WFL if it was successful. When I flew home to Hawaii I would fly through Los Angeles and very often would have meetings with one or both of them and they would let me know what the NFL was moving towards.

O.J. Simpson was the one who told me why the colored pants wouldn't work. Of course, the colored pants were to act as a sorting process you could see a wide receiver streaking down the field and linebackers blitzing because of their pants. O.J. told us that great running backs always look at the legs of their adversary when they run. So when we tested the pants we found that it confused the running backs dramatically, therefore it was an idea that never materialized.

HOF: When John Gilliam jumped back to the NFL from the WFL's Chicago Winds did the league take any action to prevent his move?

CH: We didn't take any real action at all. There was a lot of bravado. We were little kids trying to play a big kids game. We had all these terms and concepts that the NFL had established and we tried to apply them to a new league and to rookie owners. There was a certain air of inexperience in the front office, with our general managers… so, when we talked about taking action there wasn't a sense of cohesiveness or collective strength. This is the type of concern that will be addressed by the single entity XFL. In 1975, we just didn't have the collective strength. The owners who had the financial reserves resented the owners who did not.

HOF: How much pressure were you under to make the WFL a success in 1975?

CH: Tremendous pressure to make it successful not only from the owner's standpoint but also from the communities involved as well. Some of those communities reluctantly took us in and gave us a place to play and supported the league. In 1975, we were just trying to right a wrong. We were trying to get players paid who hadn't been paid in 1974; we had to negotiate settlements on stadium rents and airline transportation that hadn't been paid. It was a very difficult problem for us. The media felt that they had been exploited by the WFL in 1974 after supporting us, and this exploitation, or feeling of exploitation after assisting the league in its development was unfair. So, again, our theory of 'righting a wrong' was probably right, but to right a wrong you need to put into the equation a variable of time. In retrospect, the World Football League shouldn't have continued in 1975 unless we had a five-year plan to achieve success.

HOF: It was reported that CBS was interested in televising WFL games in 1976. Was there any truth to that rumor?

CH: We were discussing a 1976 television package with CBS, and there was some keen interest from the network but we never fulfilled the requirement finishing the 1975 season.

There was a lot of talk about television in 1975, but we didn't really have anything to offer the major networks. We were coming off of bankruptcy, going into communities where we could get some level of acceptance, and trying to get players paid for their efforts. It just wasn't the type of product that was particularly attractive to these people.

In 1975, we were dealing with the forerunner to ESPN. Eddie Einhorn was very interested in the WFL and we talked about this at great length. There was some local television coverage of the league, but one of the problems that we had was that the properties of the WFL were done by the individual franchises. Every one did what they wanted and when they wanted.

HOF: In 1975, the Chicago Winds of the World Football League negotiated with All-Pro, New York Jet quarterback, Joe Namath. In your opinion, how crucial was the signing of Joe Namath to the WFL, its survival, and securing a national television contract?

CH: At the time it appeared to be that way. We, of course, were trying to get a significant television contract and we were led to believe that Joe Namath was key to that becoming a reality. I think more than anything else, Namath was symbolic of our stepping forward in a manner where knowledgeable people and great talents would see us as a viable long-term investment, whether they were investing their talent or their money. So, to have a major investor such as Joe Namath coming in to invest his time and talent in the league was very important to the WFL and the promotion of the WFL as an entity. When Joe Namath turned us down it focused more negative energy on us, and, at that time, things were so public that the media took a hold of the situation. Namath was more public about declining the WFL offer than was Walter Payton.

HOF: The World Football League negotiated with Walter Payton?

CH: Oh yeah. I got a call from Gene Pullano, who was the owner of the Chicago Winds, and I flew in from New York to Chicago. Pullano called and said, "I've got this kid coming out of Jackson State and I'd love to sign him into the World Football League. Would you come down here and help me recruit him". Gene and I talked about this and I agreed to come to Chicago and assist with the negotiations. I went to the meeting and sat in with Walter, his agent, and Gene Pullano for about two hours. This guy, Gene Pullano, was a pretty high-flying, promoter type of gentlemen and I remember him taking off a big diamond ring that he had and giving it to Walter Payton. So, I said that I was heading back to New York and would be pleased to drive Walter back to the airport and we could discuss the meeting. As I was driving to the airport I asked Walter, "Have you ever had any great dreams or desires? What is your goal in life? Walter replied, "I've always dreamed of about wearing a NFL uniform and playing in the National Football League." I said, "Well, why are you talking with us? He said, "It might be to my economic advantage to sign with the WFL. I could make a little more money." I said, "Walter that is not the way to start out. Follow your dreams in life don't pursue dollars. The pursuit of money is not going to get you anywhere. The pursuit of goals and dreams, that's where you should spend your time. Very frankly, if you have those dreams and desires, and those are your long-term goals, you should pursue them. Go in the NFL and become a great player, and if some day we make it as a league, come back and go with us."

Every time I saw Walter Payton after that day, until he died, he would come up to me and mention that car ride to the airport when we talked about his dreams and goals, and how it changed his life.

I had a unique feeling about this young man. I wasn't in the business of finding great talent and turning then away from the WFL. In fact, he was the only person I ever said that to. He had such a wonderful manner about life, and he had serious philosophical beliefs that were fascinating, and that's how we got on this talk about his personal goals.

HOF: Towards the end of 1975, the WFL was facing problems that were too big, you called a meeting in New York City regarding the future of the WFL?

CH: We brought all the owners together because we agreed that we would put the together in two half-seasons. Then we would have a review of where we ended and where we were headed and make the needed adjustments and move forward from there. We had a very formal review process. That meeting was the review session, and all governors were present from all the cities.

The attendance was abysmal. I remember going to Philadelphia for a game with my son and I mentioned to him that we should get up close to the stadium because I didn't want to get caught in traffic, I had an interview to do before the game. So I suggested we go for a pizza near the stadium, and that's what we did. After eating, as I walked with my son to the stadium, I went up to a policeman and said, "Excuse me. Can you tell me where the stadium is? He said, "Yeah. It's right across the street." I said, "I thought it was in this area. But, where are all the people?" I'll never forget what he said. He looks at me and he said, "There are none." I said, "Is anyone here?" The policeman said, "No."

I entered Franklin Field and there was 500 people sprinkled around the first level of the stadium. I knew right then and there that the process of 'righting an old wrong' and having strong owners, we had a strong owner in Philadelphia, was going to be a long-term process. So, the meeting in New York focused on our ability to penetrate the market. Unless we could attract the fans and see signals of support from the communities it would be ridiculous to plow forward. Not only did the ownership group report a lack of support in the communities but also a lack of support from the local governments. The politicians and local authorities came down so hard on the franchises due to past deeds that they weren't going to let us up. Without their support, or a resemblance of support, it was an up-hill battle that we couldn't fight. The owners felt that this wouldn't correct itself in time.

HOF: Which of the teams voted to continue the WFL season?

CH: I think at the time we finished there was very little support to continue. John Bassett of Memphis wanted to scale down and have a league of about four to six teams. We thought that was so out of line that no one would take us seriously. On the other hand, John's concept of going forward was to have the owners of the teams' that were having difficulty to simply struggle through until they turned their franchises around. These owners weren't prepared to do it. I think the reason they didn't was because the element of fun, or excitement was gone. When the excitement is reduced to staving off economic problems the cost doesn't out weigh the benefit.

(WFLHOF note: The media reported that San Antonio, Southern California, Charlotte and Jacksonville voted to continue with the season. This has been disputed, and other accounts have Memphis, Birmingham and Southern California voting to continue.)

HOF: When the World Football League closed it doors in 1975, what were your memories of that day?

CH: On October 22, 1975, the day we announced the closing of the World Football League, that night our offices, which were in the Time Life Building in New York City, were raided. All the film footage, tickets, everything that had some value was gone. I have a few things; footballs, sports illustrated articles, and such. All the items we had that had any value at all were taken that night.

HOF: How would you like the World Football League to be remembered in sport's history?

CH: The league was, for me, one of the most exciting things I have ever done in business and in life. The excitement of our first practices in Riverside, California, as the athletes went through their workouts in that incredible smog they had there. The initial league meetings in Newport Beach, with the grand celebrations, gave you a feeling of being involved with something historical. The day the WFL announced its reorganization, against all odds, and we held our meeting in New York City and Larry Csonka and Calvin Hill talked to the media about the game of professional football and its place in the community. All of those memories are very important to me, and I'll never forget them.

The WFL was an opportunity for everyone to create something that would last the test of time. The league should, and will, serve as a beacon to the importance of committing to a business plan and seeing it through. We did have a very positive impact in some of the communities and I think we will be remembered for that.

NOTE: The Chris Hemmeter interview was conducted by Jim Cusano and Richie Franklin. This interview appeared on the former WFL Hall of Fame Website, and is used with permission. This interview is the property of the World Football League Website and may not be used without the permission of the Website owners.

© Copyright 1996-2007 Robert Phillips, All Rights Reserved